Inside a brightly lit laboratory on UNLV’s campus, science fiction is on its way to becoming reality.

Cell regeneration, an organism’s ability to self-heal and regrow entire organs and limbs after severe injury, is typically the stuff of superhero lore.

From the Greek myth of Prometheus to blockbusters such as “The Wolverine” and “The Amazing Spider-Man,” the regenerative capabilities of hero and villain alike captivate audiences.

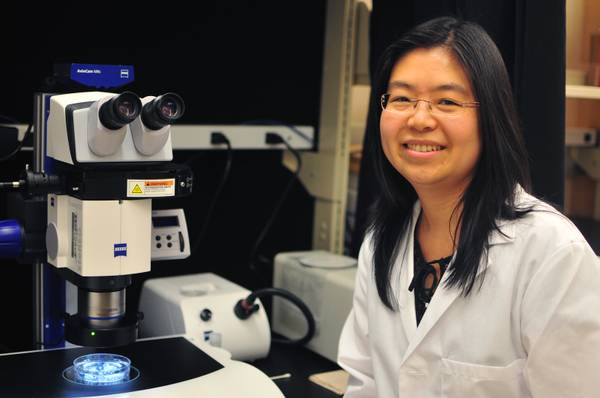

It’s also piqued the interest of UNLV assistant professor Kelly Tseng, who a year ago moved to Las Vegas to lead the university’s research in cell regeneration. The Harvard- and MIT-educated researcher has been studying tadpoles’ ability to regrow their tails after they have been severed and what signals trigger cell regeneration.

The Sun sat down with Tseng this week to learn more about her research:

What animals have a regenerative ability?

Most people don’t know that tadpoles can regenerate their tails — and very quickly. It usually takes seven to 14 days. Planaria, which are flatworms, can be cut into pieces, each of which will regenerate. Zebrafish can regenerate their heart, even if on-third of it is cut away. Antlers of a moose can grow two centimeters a day, which is the fastest rate of organ regeneration. Salamanders are basically the champion of regeneration. They can grow back a limb, a tail, their retina, even part of their brain.

It’s really amazing, all these animals with abilities we would like to have.

Do humans have this capability?

The liver has some regenerative capability. Children, 12 years and younger, can regenerate their fingertips if it’s above the nail. It’s pretty spectacular.

What kind of tadpoles do you use and how do you test their regenerative capabilities?

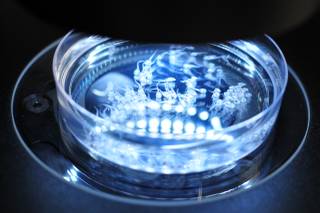

We use South African frogs because they are considered a model organism to study, like fruit flies. We ship them here from a frog farm in Wisconsin. They’re an invasive species, so we have to be careful. We keep tight control on them.

We put tadpoles to sleep by dropping anesthesia into their petri dishes and then use a scalpel to cut off their tails. We want to make sure they’re not in pain so we treat them well. Within seven days, their tails regenerate.

What have you discovered so far about regeneration?

Stem cells are cells with self-renewing abilities. With the proper instruction, they can be assigned to become different cells.

Some scientists are looking at ways to create stem cells. We’re not looking at that at UNLV. We’re doing basic research on the natural process of regeneration.

In particular, we’re asking: Once you have these stem cells, what can you do with them? What instructions can we give them? That’s what our goal is: to learn how tadpoles regenerate. We’re looking for signals that tell tissues, “Hey, we’ve lost a big chunk of an organ. We need to initiate regeneration.”

What kind of signals are you looking at to trigger regeneration in animals?

There are many different types of signals: bioelectrical stimuli, gene manipulation and pharmacological drugs. We can use ions as signals. I found that an infusion of sodium ions can help tadpoles promote cell regeneration. Salt is a key signal for tadpole regeneration.

There are chemicals that shouldn’t be used in regeneration. One of my students discovered that methylisothiazolinone, which is found in some shampoos and cosmetics, can cause regenerative defects in tadpoles.

What human applications are there for your research?

People have studied regeneration for hundreds of years. It’s always fascinated everyone, but we don’t know how it happens naturally. Now we have the tools to really study it.

We’re doing basic research on the natural regenerative process of tadpoles and how it occurs. Hopefully, they can give us insight for potential therapies down the road for humans. It’ll take time. Human bodies are very complex.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy